I have been working on this for a while now and figured I should share some of it with anyone who might be interested. I am hoping to self-publish this sometime this year, assuming nothing bad happens …

Let me know if you like it or if you have any useful feedback.

To understand how a nuclear reactor works, we need to understand a little about how an atom is constructed and the forces that are at play inside it.

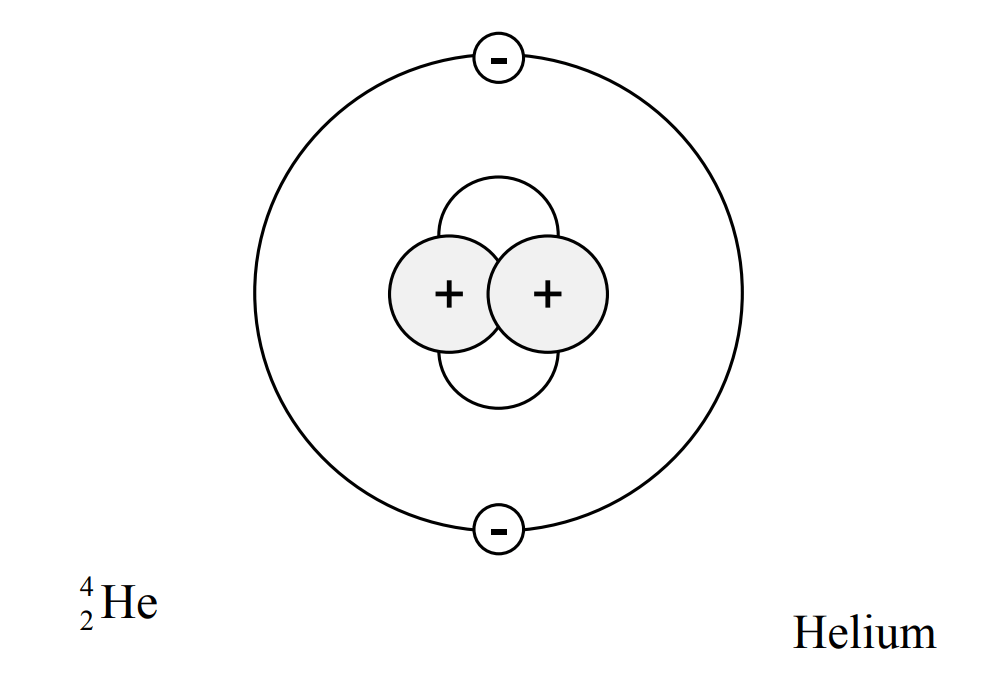

Atoms consist of a nucleus at the center, and a cloud of electrons that exist in a kind of shell around the nucleus. The nucleus itself is made of two particles; neutrons, which have no electrical charge, and protons which have a positive electrical charge. There are generally the same number of electrons as there are protons.

The most basic atom is that of hydrogen. Hydrogen has a single proton in its nucleus and no neutrons. One solitary electron is zipping around it. The number of protons in an atom determines the element and is called the atomic number. The atomic number for Hydrogen is 1.

The next element on the periodic table, with an atomic number of 2, is Helium. Helium has two protons and two neutrons in its nucleus and two electrons to accompany them. See the figure below.

https://www.standards.doe.gov/standards-documents/1000/1019-bhdbk-1993-v1/@@images/file

As elements grow more complex, the number of protons and neutrons rises. Uranium has ninety-two protons, so its atomic number is 92. But different forms of the same element can have different numbers of neutrons. This is known as an isotope.

Uranium’s most common isotope is U-238. The number after the dash is the atomic weight of the element and is the sum off all particles in the nucleus. Since uranium must have ninety-two protons to be uranium, that means the rest of the two-hundred and thirty-eight particles must be neutrons. So U-238 has one-hundred and forty-six neutrons.

The isotope of uranium we use most often in nuclear reactors is U-235, so it has three fewer neutrons than U-238, but must have ninety-two protons or it wouldn’t be uranium at all.

Atomic Forces in the Nucleus

This relationship between the number of protons and neutrons is important to our understanding of how atoms behave. This is because there are various forces acting within the nucleus of an atom. Some of those forces want to tear the atom apart while others are straining to hold it all together.

The first force to consider is a concept that many people will find familiar. Protons are positively charged. Objects with the same charge repel each other in the same way two north poles on a magnet will push away from each other. As it turns out, electricity and magnetism are two sides of the same coin, but that is another book worth of information that I couldn’t fully explain if I tried.

This is called the electrostatic force of repulsion. It is a strong force that acts over long distances and is continuously trying to destroy every single atom more complex than hydrogen.

So how do elements with more than one proton exist? There must be something counteracting the repulsive force of the protons.

As a matter of fact, there are two things trying to hold the atoms together.

One of them is gravity. The force of gravity is present around any object that has mass. Right now your own body is exerting a gravitational pull on all the objects around you and they are tugging right back on you. The reason that objects don’t come flying off shelves towards us is that our mass is insignificant when compared with the mass of the entire earth that is also pulling on everything.

When we get to the atomic level, the masses of the particles are so tiny that we can safely ignore gravity for the rest of this discussion.

The other force that allows atoms to exist is the strong nuclear force. This is a very strong force, as the name suggests, and exists between any two particles in the nucleus of an atom. However, it is very short ranged. The strong nuclear force mainly operates between two nucleons that are next to each other.

When the strong nuclear force is more powerful than the electrostatic force, an atomic nucleus will be stable. When this arrangement is swapped, the protons win the fight and the nucleus will be unstable. In order to become more stable, a nucleus will emit radiation of some type to try and move closer to stability.

The electrostatic force builds up more quickly and acts over a much larger distance than the strong nuclear force, which means that as we continue to add protons to an element, it becomes more and more unstable. To balance this out, the number of neutrons in an element rises faster than the number of protons do, adding more to the strong nuclear force.

Nuclear Stability

The largest completely stable element that we know of is lead, specifically Pb-208. Lead has an atomic number of eighty-two, which means Pb-208 has one-hundred and twenty-six neutrons. This gives us a neutron to proton ratio of 1.54. U-238, with its ninety-two protons and one-hundred and forty-six neutrons has a ratio of 1.59.

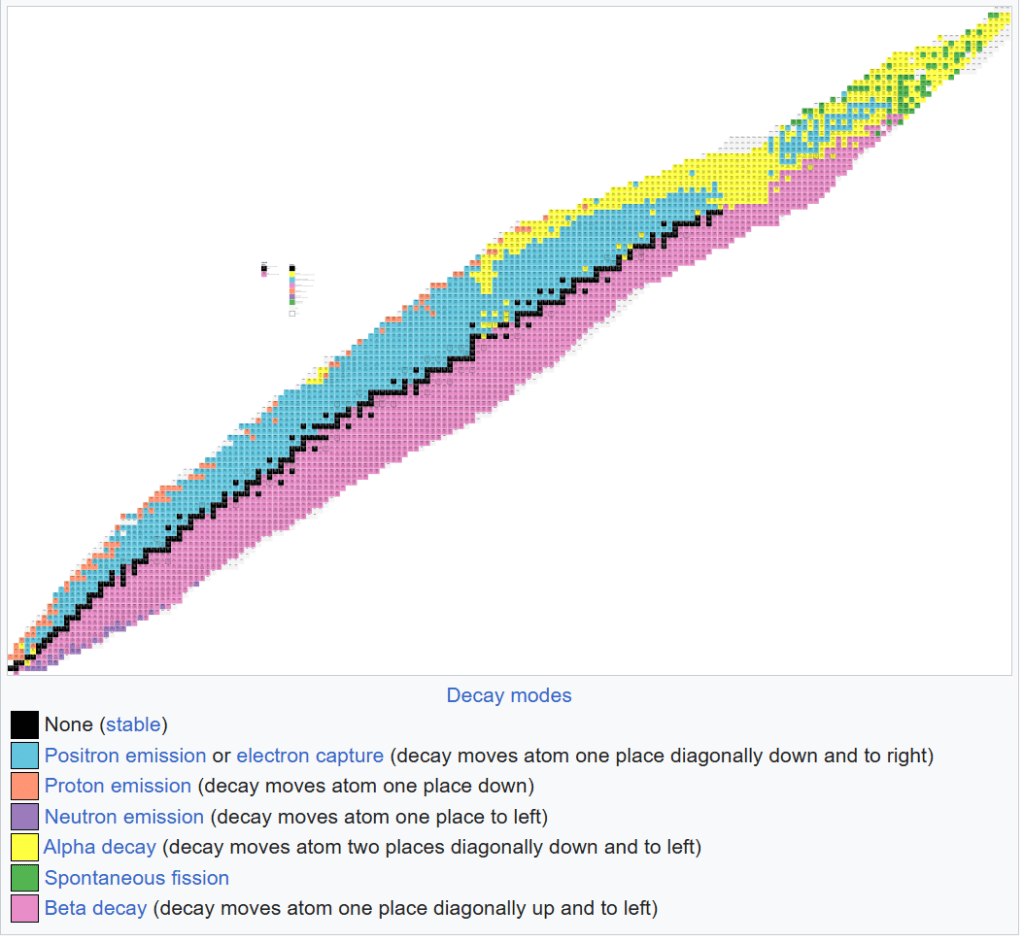

The table below shows this concept visually. The x-axis (horizontal) is the number of neutrons and the y-axis (vertical) is the number of protons. The black squares are stable isotopes and we refer to the line they make through this graph as the line of stability. The other colors are unstable and show the type of radiation that each unstable isotope is likely to experience.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Table_of_nuclides

Up to an atomic number of about twenty, which is calcium, there is a one to one ratio of protons to neutrons. You can see this as the black boxes form a straight line up to that point. As we move up and to the right, the number of neutrons grows faster than the number of protons and the black line curves to the right.

If we zoomed in we would see that the black square furthest up and to the right is Pb-208. As stated earlier, this is the largest isotope that is known to be stable. Everything past that point is unstable to a greater or lesser extent.

Radioactive Decay

Different unstable isotopes prefer to radioactively decay (this is what we call emitting radiation and becoming another element) via different forms of radiation. This is a statistical function, more like the odds of one kind of radiation being emitted versus another than an absolute. The same element may decay via neutron emission most of the time, but also have a chance of emitting a beta particle.

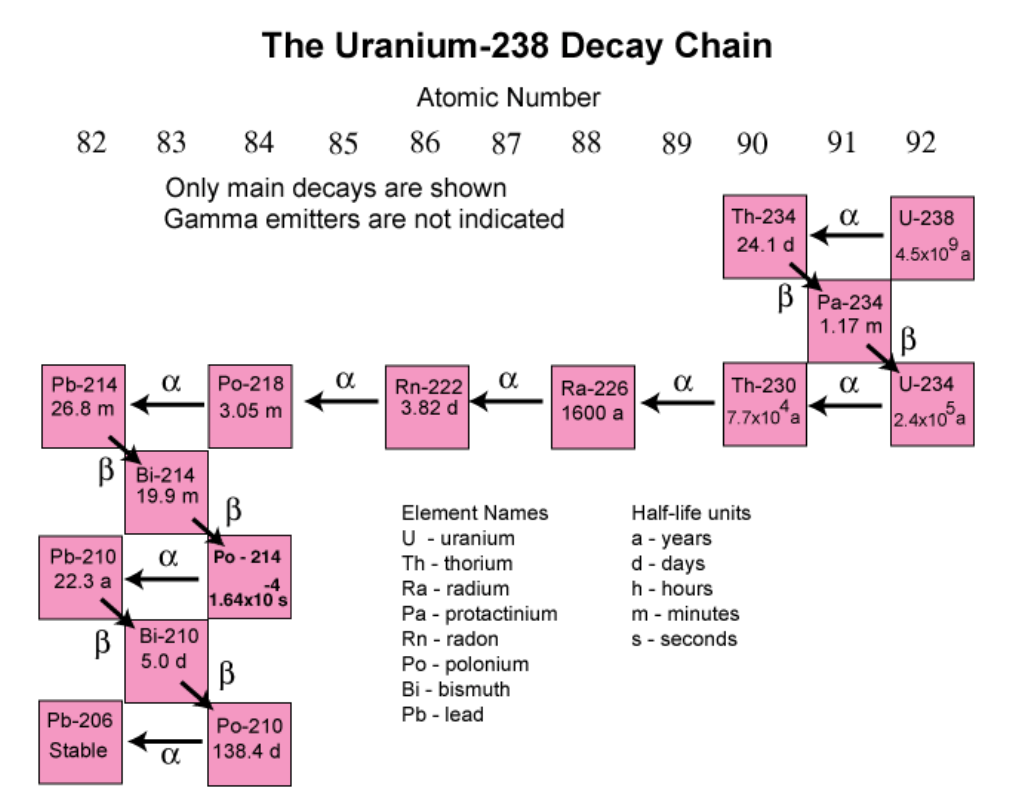

Each kind of radiation that is emitted causes a different change in the atom that is trying to become stable. We will follow U-238 as it is such a relevant isotope for this discussion. We refer to this process as the decay chain for a specific isotope. Below we see the decay chain for U-238.

https://www.epa.gov/radiation/radioactive-decay

U-238 has a half-life of 4.5 billion years. The half-life of an isotope is the amount of time it would take for half of a sample of that isotope to decay into some other element. So if I had a pound of U-238, then waited 4.5 billion years, half a pound of the original sample would still be U-238 and half would be some other element.

U-238 decays mainly via the emission of an alpha (α) particle. An alpha is essentially a helium nucleus, containing two protons and two neutrons but no electrons. By releasing this particle, our U-238 goes down two atomic numbers from 92 to 90. Atomic number 90 is thorium. We also lost two neutron, so the atomic weight drops by four, from 238 to 234. We now have Th-234.

Th-234 decays by emitting a beta minus (β-) particle, which is when a neutron becomes a proton by emitting an electron. An electron has a negative charge, so by releasing that charge the neutron becomes positively charged, which makes it a proton. So our Th-234 has turned one neutron into a proton, for an atomic number of 91. We now have Protactinium-234 because we didn’t lose any particles from the nucleus.

Pa-234 also decays via β-, so it moves up one more atomic number, back to ninety-two, which means we are back at uranium, but this time it is U-234.

U-234 alpha decays into Th-230, which alpha decays into Ra-226, then Rn-222, then Po-218, then into Pb-218. It then jumps between alpha and beta minus decay until it reaches Pb-206 and is finally stable.

The other options for radioactive decay are less common. The isotope can emit a proton, a neutron, or beta plus (β+) decay by emitting a positron (like an electron, but positively charged). It can absorb an electron or it can even spontaneously fission. Each time it goes through this process, it becomes something new.

Neutron Induced Fission

These are natural forms of radioactive decay. In order to produce the amount of energy we need, we need to force uranium to fission billions of times a second. We do this by shooting neutrons at the uranium nucleus. Sounds simple enough, right?

We are talking about nuclear physics, so nothing is ever that simple. There are several things that can happen when a neutron interacts with the uranium atom. It can simply bounce off. It might be absorbed, but being absorbed doesn’t guarantee that a fission will result. It also might just eat our neutron and then undergo a decay chain that doesn’t result in fission, essentially wasting the neutron as far as our reactor is concerned.

It turns out that some isotopes are more likely to fission than other isotopes. An isotope that will more than likely fission whenever it grabs a neutron is called fissile. The pickier isotopes that will only fission for very specific neutrons are referred to as fissionable.

U-238 is fissionable. It will fission if it absorbs a neutron with enough kinetic energy. This is called the critical energy. But most neutrons are not moving fast enough to cause this to happen, so the majority of neutrons that U-238 grabs are lost to the fission process for now. They can become other fissile isotopes, like Pu-239, but that is not the primary reaction.

U-235 is fissile. It still has energy levels it prefers, but overall it will fission after absorbing just about any neutron that happens to hit it. As a matter of fact, it prefers the slower neutrons.

This concept is why enrichment is a thing. Natural uranium is made of 99.3% U-238 and only 0.7% U-235. There are a few other naturally occurring isotopes, but they aren’t common enough to worry about. This is referred to as the natural abundance of an isotope. You can build a reactor that uses natural uranium, but that is a different chapter. In the US, we use enriched uranium.

Enrichment is the process of taking the 99.3% to 0.7% mix of natural uranium and raising the percentage that is U-235. This is done by the use of those centrifuges you are always hearing about on the news when Iran comes up. The uranium ore is turned into a gas, which is then spun at thousands of RPM. This spinning forces the heavier U-238 atoms to the outside of the centrifuge and the lighter U-235 atoms into the middle. By doing this many times over, you can concentrate the U-235 to higher and higher levels.

Civilian reactor fuel is limited to around 5% U-235. Some newer designs are approaching 20%. Nuclear weapons grade fuel is much higher, around 90% or more.

By increasing the amount of U-235 in our reactor fuel, we increase the chance that we can cause a fission to occur. This still leaves the fuel at 95% U-238, so we do lose some neutrons to U-238, but it is sufficient for sustaining a chain reaction when placed into the right geometry inside a reactor.

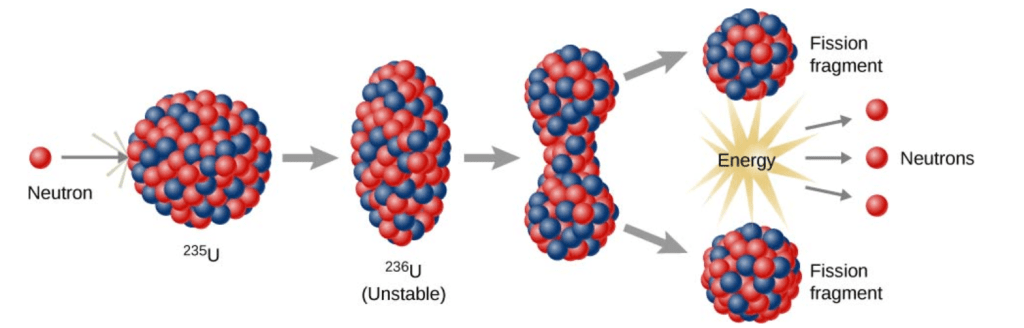

When a neutron is absorbed by the U-235, all of the energy it was carrying with it as it zipped around the reactor is added to the nucleus. This makes the already unstable nucleus very unstable. The best analogy for this is the water-drop.

https://pressbooks.online.ucf.edu/osuniversityphysics3/chapter/fission/

In this model, the nucleus is pictured as a sphere. When the neutron is absorbed, the sphere becomes excited and unstable and begins to warp. A neck forms between two clumps of nucleus. When this neck splits apart, fission has occurred. This releases fission fragments, energy, and some additional neutrons. This is a simplification, but it gives us a way to visualize the process and is sufficient for this book.

The additional neutrons that are released are key to successfully creating a chain reaction. If no neutrons were emitted from the fission, we would get exactly one fission and nothing further would happen. But U-235 tends to release two or three free neutrons each time it fissions, providing the extra neutrons we need to cause a chain reaction.

You can see the exponential nature of the chain reaction. Each fission releases two neutrons. Those two neutrons go on to cause fission in two more atoms. Now we have four neutrons flying around, which hopefully go on to make four more fissions and eight neutrons. Keep this process moving along and you are very quickly getting the billions and billions of fissions every second that we need to make useful power.

So that is how we make a fission chain reaction occur. There is obviously a lot more to it, but the short version is we shoot the right element, U-235, with a neutron. That U-235 splits apart and releases energy and more neutrons to keep the process going.

Next, we need to understand where that energy comes from. For that we are going to need Einstein’s help.

Leave a reply to katenewbill Cancel reply