I spent 2 years of my life being trained to become a Senior Reactor Operator (SRO). Hundreds of hours in the classroom, hundreds of hours in the simulator, and at the end, a 2 week long exam given by the NRC. For what? What exactly do nuclear operators do that requires all that training?

As it turns out, not that much. I’ll attempt to describe a typical day in the control room of a nuclear power plant, but keep in mind that nuclear power is one of those jobs that is best when it is painfully boring. We don’t like excitement.

First a breakdown of the people involved. Each reactor plant (we’ll call it a unit after this) control room has 3 licensed operators in it. One is the Unit Supervisor (US), an SRO who has supervisory oversight of the unit. There are 2 Reactor Operators (ROs). They have an RO license from the NRC and are the people actually touching the buttons and knobs to do the work. One is usually pretty new. Their job is mainly to watch the reactor continuously. The senior RO runs work for the shift, and helps with the monitoring.

There are 2 additional SROs. One is the Shift Technical Advisor (STA). This position exists because of the accident at TMI. The STA is someone with an engineering degree and usually an SRO license. There are there to provide an independent look at everything we are doing with a focus on protecting the core, especially if anything goes wrong. When things are not going wrong (which is most of the time) this person helps process work and interfaces with other departments so we don’t have too many people marching into the control room.

The other SRO is the Shift Manager (SM). They are the senior SRO and have overall command of the shift. They also interact with senior station leadership and go to tons of meetings. Their most important function is to provide oversight for the control room crew. No one knows everything about the plant, so as a Unit Supervisor, it is really nice to have someone more senior there to bounce things off of.

Shift starts ate 0530, but you have to get there about 30 minutes early for turnover. This involves the person you are relieving telling you everything they did that night. They give you a complete status of the plant, everything that is broken or just acting a little weird. Then you walk down the control panels together, making sure you have an accurate picture of the nuclear reactor you are about to assume responsibility for. You find the things they forgot to tell you and ask questions to make sure you know why things are the way they are.

Once that is done, you relieve the person so they can go home and get some sleep. You settle in at your desk and start looking at the schedule for the day. On some days there might be almost nothing to do. On others, the schedule is packed and you already have a headache. We review the schedule weeks before it is implemented, and we are supposed to balance it. Some are better at this than others, so some days are a little busy.

At 0600, once everyone in the control room has relieved, you have a meeting. All the SROs and the senior ROs gather to discuss the days plan. The Shift Manager lays out his expectations for the day, and we hand out the paperwork. Seriously, there is so much paper. If Greenpeace knew how many trees we kill, they’d stop protesting the reactors and come after us for that. (A lot of plants are transitioning to electronic work processes using surface pros or ipads, so this isn’t as bad as it used to be.)

The RO heads to his desk to get the work ready to go. This involves printing more things, like procedures and forms, and giving the non-licensed folks who do the work outside the control room copies of everything. The RO will then walk down the procedure, making sure they know where all the switches and indications are, and that the plant is in a condition to support the work.

The Unit Supervisor looks over the work as well, looking for conflicts. When you plan the work, you don’t necessarily know the exact plant conditions that will exist that day. There are rules on what equipment you can have out of service (OOS) at the same time (I did a post on tech specs that explains this). The SRO compares the planned work that day to the stuff that is broken or otherwise OOS. If there is a conflict, they start making phone calls to work through it, or cancel the work if it violates the rules. (An example of this would be diesel generators. Each unit has to have 2. If you planned to work on DG-A that day, but DG-B is broken, you can’t take DG-A OOS.)

The kind of work we do on a shift is split between maintenance and required testing. The maintenance is largely preventative maintenance (PM). You take stuff OOS to perform work to keep it running well. This is the same idea as an oil change and tire rotation for your car. It keeps equipment it top shape and prevents us from having to deal with things breaking.

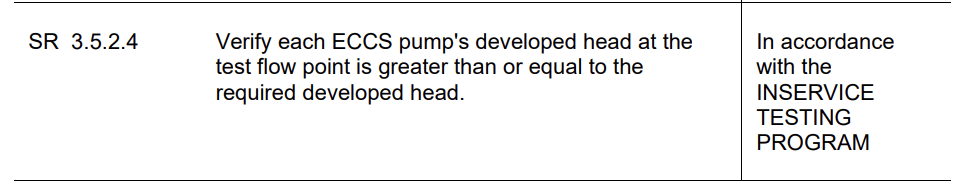

The required testing is part of tech specs. Tech specs have something called surveillance requirements. Below is an example. This is for the Emergency Core Cooling System pumps. They put water back in the reactor if there is ever a big leak. Every so often, you have to start the pumps and make sure they develop enough head (basically pressure) to do their job. The in accordance with statement is what tells you how often you have to do it. A lot of them have definite times, like once every 30 days. Some, like this one, refer to another process (inservice testing program in this case) because the frequency can change depending on circumstances.

At 0700, the entire crew meets in the control room. There are usually 5 to 7 people who work outside the control room. We’ll call them non-licensed operators (NLOs). These are the folks that turn valves and operate things that aren’t controlled from the control room. We discuss the schedule and expectations for the shift.

Once that crew meeting is over, the day really begins. The rest of the site shows up around 0700 and are lined up asking to start work by 0730. No one does anything on a unit without the permission of the Unit Supervisor, so you spend a lot of your time looking at the work other groups want to do and making sure it won’t conflict with anything else happening. It’s one of the reasons being an SRO is so hard. You have to understand instrumentation well enough to know the work an Instrument Tech wants to do won’t get you in trouble. The same goes for mechanics and electricians and everyone else on site. You have to be a jack of all trades and you are ultimately responsible for everything that happens on your unit.

Once the RO is ready, you start doing your own work. The SRO stands back and provides oversite, just watching and ensuring they are doing it correctly. This involves coaching them to the standards. You don’t just get to touch a switch in the control room. You have to read your procedure step, you have to read the label, you then compare the two. Once you do that, you ask the other RO for a peer check. He reads the step, reads the label, compares the two, then agrees that you are on the right switch and are going to take the right action. If they aren’t doing all of this as well as they should, the SRO steps in and fixes them.

Let’ say the work you’re doing is to run one of those ECCS pumps to see if they develop pressure. This requires starting the pump. Once that is done, the RO takes readings in the control room and an NLO takes readings locally. We never trust just one indication. You plot those readings on a graph and make sure the dot is between the lines. If it is, great. If it isn’t, your day just got much more complicated.

If the pump isn’t making enough pressure, it is inoperable. Operable means it can do it’s required job. When things are inoperable, tech specs forces you to do something about it. You can’t just sit there with broken safety related equipment. Read the tech spec post for more info.

In practice, the Unit Supervisor has to call the STA and the SM to come to the control room. They will look at the test and agree or disagree with your decision. Assuming you were right and the pump is broken, the SM starts calling everyone else to get the pump fixed. The Unit Supervisor logs the exact time and date the pump failed and any actions taken as a result. This tends to wreak havoc with the rest of the schedule that day, because you can’t work on a lot of other things with this inoperable pump,

Once that mess is settled, you move on to the next job. Most days, that’s all there is. You run some things to make sure they work. You take some things OOS so you can work on them. You run the things you just took OOS to make sure they still work after the maintenance. You test things to make sure they can do the job they are designed to do. You do tons and tons of paperwork to document all of this.

Sometimes, however, things break unexpectedly. If whatever breaks causes the plant to move on you, you have to respond. This involves implementing an Abnormal Operating Procedure (AOP). The goal is to stabilize the plant. If the situation is bad enough, you might have to trip the reactor. If you do this, you go to the Emergency Operating Procedures (EOP).

EOPs verify that the reactor shutdown like it was supposed to and that all safety function are being maintained. Safety functions are things like core heat removal or reactor pressure control. Obviously, if you aren’t removing heat from that core that’s bad. The EOPs have actions to restore any safety function that is being challenged while protecting the core from damage.

AOPs and EOPs almost never happens. Most units trip once every 2 to 3 years. Most trips are uncomplicated. You check all the safety functions, they are all satisfied, and you leave the EOPs for normal procedures to finish shutting down the plant. I was on shift for 2 years and never entered and AOP or an EOP. It just doesn’t happen that often.

It’s one of the funny things about nuclear power. You spend most of your time training for things that will never happen, because the consequences of not being ready are so high. Lack of training played a huge role at Three Mile Island, and we decided to never let that be the case again.

At some point that day you probably ate lunch at your desk, or standing up watching work happen. You might have had time to document an observation of the crew’s performance, or approve time sheets. By 1600, all the work is done and you get ready to turn over to your relief. Your brain feels like mush and you are ready to go home and fall in bed so you can do it all over again tomorrow.

Leave a comment