The Three Mile Island accident is regarded as the worst civilian nuclear event in US history. Due to a combination of equipment failure and operator error, a reactor core that had only been online for 3 months was destroyed, resulting in a radiation release and widespread panic.

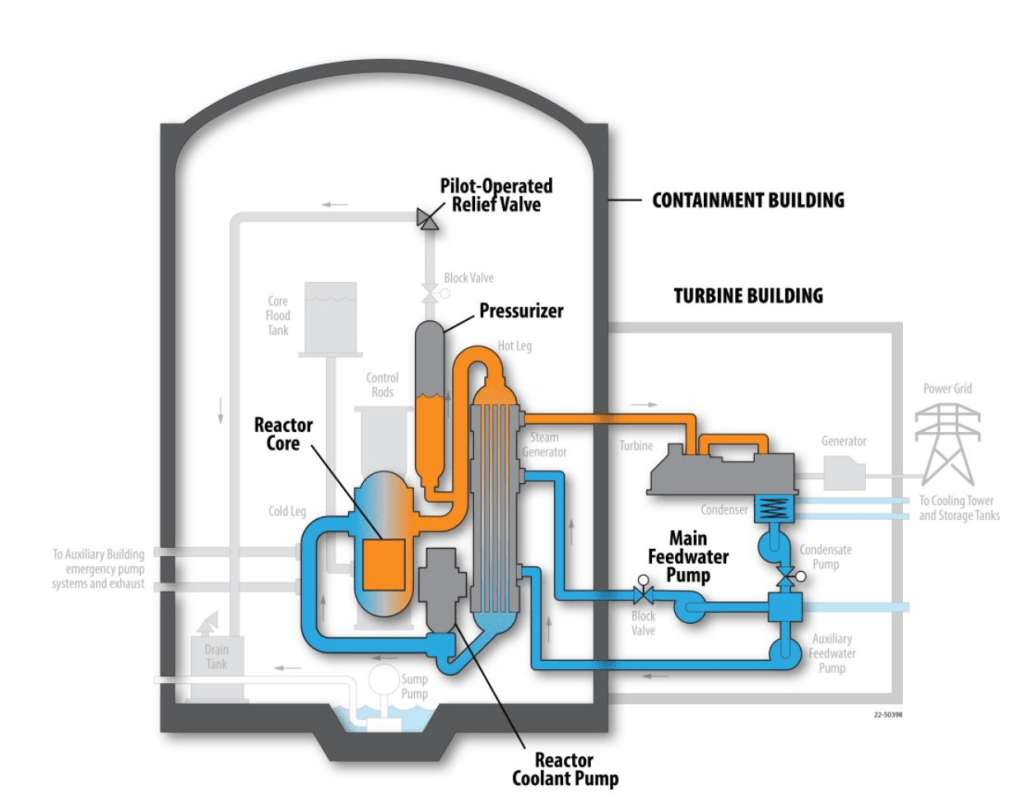

TMI Unit 2 began commercial operation on Dec 30, 1978. The accident occurred in March of 1979. The initial event was a loss of feedwater to the steam generators. Steam generators (SG) remove heat from the reactor coolant system (RCS), turning the water in the secondary loop into steam to turn the turbine. This takes a huge volume of water, and losing this feedwater causes a loss of heat removal and a reactor scram.

When the feedwater system tripped, the RCS rapidly heated up. This heat-up caused a pressure spike to occur in the RCS. A pilot-operated relief valve (PORV) opened to relieve this pressure and prevent RCS piping damage. When pressure fell, the relief valve failed to fully close. Unfortunately, the indicating lights for the valve showed it was closed, so operators were unaware they were losing coolant.

This caused a loss of coolant accident (LOCA) to begin. Water was leaving the RCS through the open relief valve. As pressure in the system fell, automatic safety systems started to replace the lost coolant. These pumps kept the core covered and ensured it remained cooled. Operators would eventually turn them off. If they had not done so, no core damage would have occurred.

As pressure in the system lowered, the water in the hottest part of the core turned to steam. This created a bubble under the reactor vessel head. As this bubble grew, it pushed water out of the core and up into the pressurizer. The only indication of water level the operators had was level in this pressurizer. It began to rise quickly.

Operators had been trained to never let the pressurizer become completely full, a condition known as being solid. To prevent this from happening, they first closed valves to limit the flow of water into the core, then turned the injection pumps off altogether. The steam bubble in the core began to expand. The top half of the core was uncovered and melted.

Hours later, another operator walked into the control room and recognized what was happening. Pumps were restarted and the core was recovered with water. This was far too late.

Despite melting half the core, very little radiation was actually released from the accident. No one received a significant dose from the release. NRC estimates put the dose for the public in the area at approximately 1 mrem. That’s about how much I get every time I walk around the plant. To put that into context, you would get 5 times as much radiation on a round-trip flight from NY to LA and back. The link below has some good info on the radiation dose we get from many sources.

https://inl.gov/content/uploads/2022/05/19-50403_Radiation_Dose_Comparisons_R4_web.pdf

(INL Radiation Dose Comparison)

The accident at TMI resulted in significant changes to the nuclear industry. The NRC required all reactors to install systems to measure the amount of water actually in the reactor vessel and monitor other conditions following an accident. They also drastically changed the training that licensed operators undergo before they are allowed to operate reactors. This link has some good info from the NRC on TMI.

https://www.nrc.gov/reading-rm/doc-collections/fact-sheets/3mile-isle.html

Another result of the accident was the formation of INPO, the Institute for Nuclear Power Operations. A few weeks before the TMI event, a similar plant had a very similar event happen. They, however, recognized the LOCA and took the correct actions. But, the staff at TMI was unaware of the event. INPO was formed to ensure the sharing of such critical information was never lost again. Here’s a link to their webpage.

Here are some more links:

https://inl.gov/trending-topics/three-mile-island/

https://www.energy.gov/ne/articles/5-facts-know-about-three-mile-island

Leave a comment