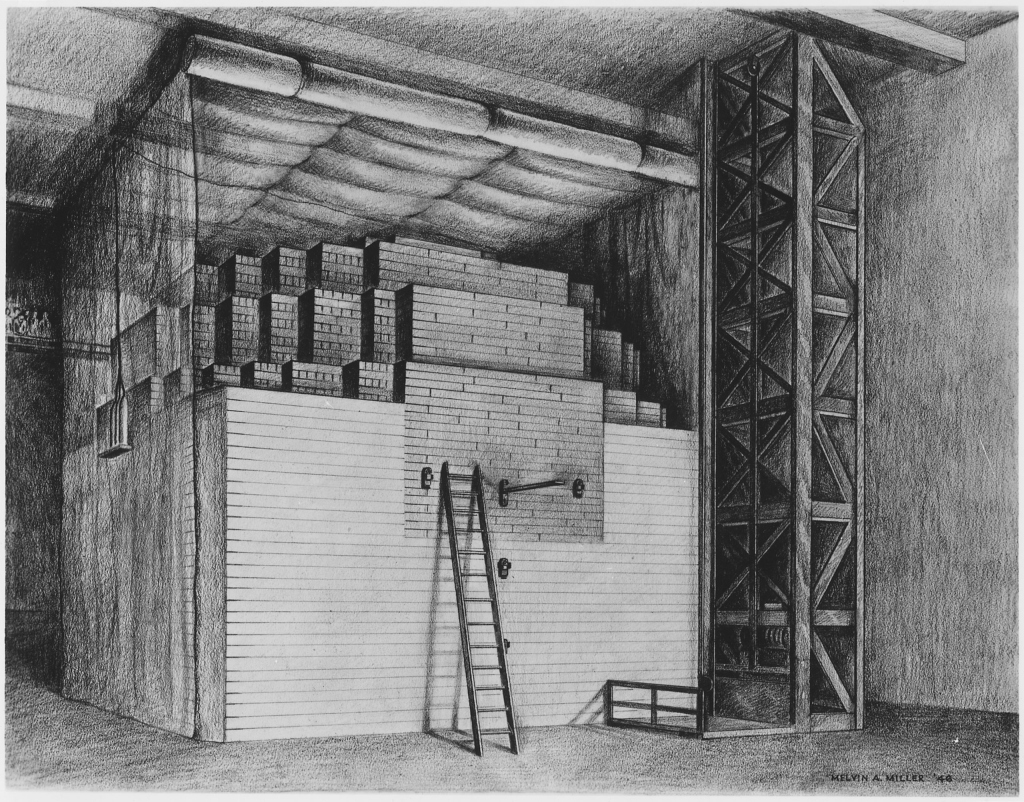

When Einstein discovered that a small amount of mass can be converted into enormous amounts of energy, he set the stage for nuclear power. The first reactor was built under the squash courts at the University of Chicago by Enrico Fermi. It went critical on December 2, 1942.

By Melvin A. Miller of the Argonne National Laboratory – http://narademo.umiacs.umd.edu/cgi-bin/isadg/viewobject.pl?object=95120, Public Domain,

Since then the world has built hundreds of commercial reactors of many different designs, but they all (so far) involve fission. Fission is the splitting of a heavy element, resulting in the formation of new smaller elements and the release of energy. This energy comes from the conversion of some of the mass of the original element, as Einstein predicted.

Atoms are made of three smaller particles. In the center, in the nucleus, are protons and neutrons. Protons have a positive charge, neutrons have no charge. Surrounding the nucleus is a cloud of electrons, which have a negative charge.

In order to split, or fission, this nucleus, we have to add enough energy to the atom to make it unstable. We do this by hitting it with a neutron. Smaller, lighter elements such as oxygen or carbon have very stable nuclei and will not fission. They will simply absorb the neutron and usually emit some other kind of radiation to release the extra energy. However, as elements get heavier, they grow more unstable.

The heaviest stable element is lead, which has 82 protons. Everything higher on the periodic table is radioactive to some degree. But, just because something is unstable, does not mean it will fission. Only certain elements will easily split. Uranium is the most commonly used, but others such as Thorium and Plutonium will also undergo fission.

Not all Uranium is equally good at this. Most natural Uranium is U-238. U-238 will fission if a very high energy neutron hits it, but more often it will absorb the neutron and decay into some other element. This is how we get Plutonium, which does not naturally exist.

A tiny amount (.072%) of Uranium is U-235. This type of Uranium will fission if hit with just about any neutron. When we enrich Uranium, we remove as much U-238 as we can, increasing the amount of U-235 in the sample. Civilian reactors use low enrichment, usually around 5% U-235 (95% U-238). Military reactors and nuclear bombs require much higher levels of enrichment, over 90% U-235 in most cases.

When a neutron hits U-235, it is absorbed, adding it’s mass and kinetic energy to the atom. Being unstable already, this is too much for the U-235 to handle. It splits into smaller elements (we call these fission products), releasing a small amount of energy as well. It also releases 2 additional neutrons, which go shooting off into other U-235 atoms to cause more fissions. Get enough neutrons flying around, and your reactor goes critical.

Unlike in the movies, this is a good thing. A critical reactor just means it is self-sustaining. Sub-critical means it’s shutdown. Super-critical means power is rising. Prompt-critical is what happened at Chernobyl, so we don’t do that.

Slowly increase the number of neutrons in your core by pulling control rods, and the tiny bit of energy from each fission adds up. The reactor core heats up, you use that heat to make steam, then use the steam to turn a turbine to make electricity.

NOTE: A lot of nuclear power is export-controlled technology. In an effort to not go to prison, everything I write about is open source. I try to link sources when I can. This one will open the Department of Energy’s Fundamentals Handbook on Reactor Theory. Great reference if you want to go just a little deeper.

https://www.standards.doe.gov/standards-documents/1000/1019-bhdbk-1993-v1/@@images/file

NOTE: This is obviously simplified. If you know more about it, great, feel free to comment. The goal is a basic understanding, not a PhD.

Leave a comment